In my previous post, Lars of Universal Aid Ukraine talked about the work of his volunteer team, conducting evacuations from settlements close to the front line. They regularly travel into areas subject to drone surveillance, artillery bombardment and FPV (First Person View) drone attack by Russian operators who would prefer a tank if they can spot one, but will happily murder humanitarian volunteers as a next best option. One day in August of this year, they almost killed UAU.

This a complete transcript of Lars’ account, just tidied a little for readability. I’ve also included his audio of the first part of the interview (further down), if you prefer to listen to that.

Lars: We don’t know exactly what it was [that hit us]. We were coming back from an evacuation close to Ukrainsk, I think two months ago now. One evac did not work out because we simply physically could not go to the place, it was just impossible. So, we only had one group of evacuees, two of them, in the second car. Me in the first car going back towards Pokrovsk.

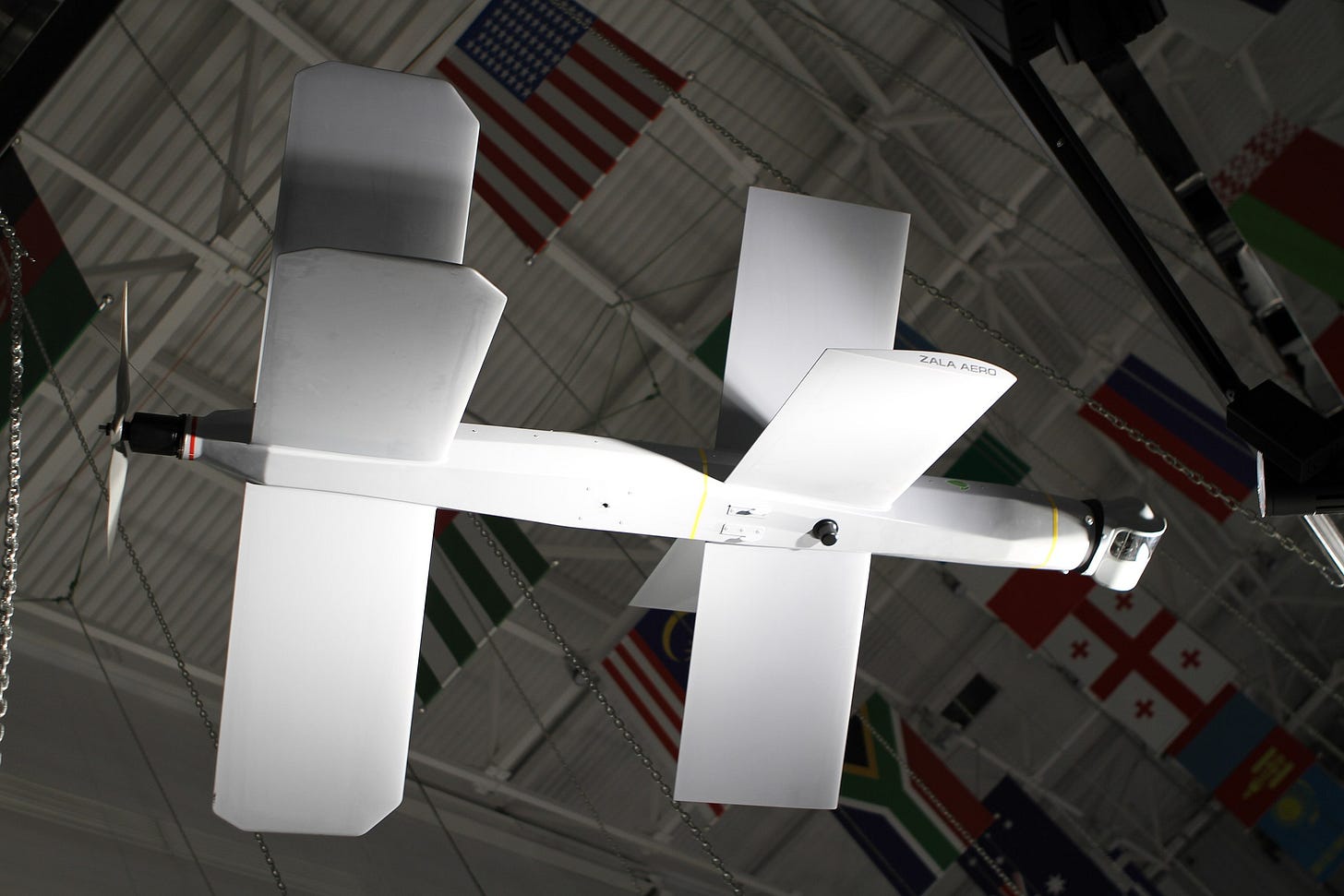

Somewhere on the highway what I think might have been a Lancet [drone] came down. It didn’t hit us, because we didn’t hear anything. Even if you're going a hundred on the highway with the windows down, you will hear artillery. Same for rockets. It's just too distinct a noise to not hear it. And the crater the impact caused was quite big for artillery; we saw it two days later when we went down to Selydove for an evacuation. It was seven or eight metres wide, and maybe a metre deep, so quite a big one. Thinking about it, maybe it was a KAB [guided bomb] that fell short. It hit about ten, maximum fifteen metres away to the right of my car.

It's hard to describe. You're just sitting, driving normally, technically already out of danger, past the blockpost, about two kilometres from the city itself. So not really expecting any danger at that point. And then from one moment to the next, it's quite bright around you, and the windshield is a lot closer to the roof. There's glass everywhere. We were like… ‘Oh.’ There was some noise as well, obviously.

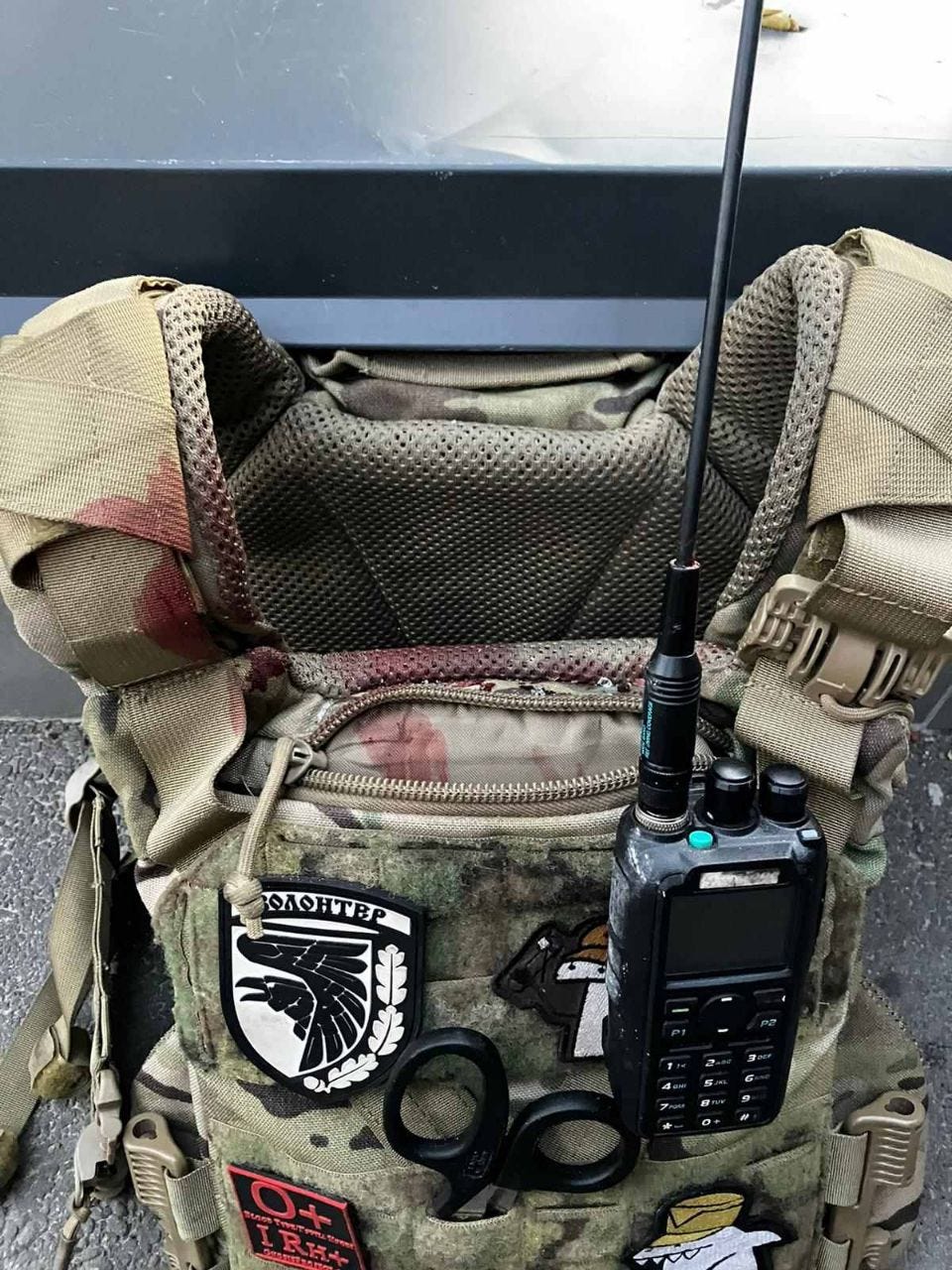

We still had ballistic glasses on, but they blew straight off our faces. Vlada’s and mine were just gone. But we had them on, which was the important part, so there was not a lot of glass in my face. Vlada got a little bit. It kind of sneaked past the glasses. And just overall, like, my right hand and arm, my left hand and left arm were full of small glass shrapnel. Some in the face, but the major problem was my neck on the right side. A piece of glass, about a centimetre long, was stuck in my neck. It had missed my artery by at best a millimetre, maybe two. It wasn't much, because the whole thing was moving with every pulse. You can still see the scar. I could feel blood running down my neck so I was asking Vlada, like, what is that? Because the mirrors were gone, so I had no way to see for myself, and I didn't want to touch it, because I didn’t know if it was really stuck in there.

So I had a lot of blood coming down my neck. It could have been arterial blood, in which case I wouldn’t have made it far. There’s not much you can do there. But Vlada checked it and she’s like, ‘No, it’s OK, it’s just normal blood. You’re not dying yet.’ Potentially.

The initial assessment was, okay, it looks good. I was actually thinking about putting some kind of gauze or something on there to stop the bleeding, which would have probably pushed that piece of glass further in. So basically killing myself. It's always a good thing not to touch that shit!

We actually kept driving. We don't have a video, but it would be interesting just to see what happened, in which order, and how little time passed. Because we were going about 100 kph along the highway, with the cars a hundred metres apart… and then it goes boom.

I know for sure that I looked at Vlada to check if she’s still alive, asked her what’s going on. She said she was OK. Then I saw the duster passing me by. OK, that's awkward: maybe they were hit significantly worse, and someone's dead in the car. They had the two evacuees, and two of our team, flying by at crazy speed. I was like, ‘Hmm, better catch up.’

But I noticed my car ain't moving anymore. My foot was on the gas, but nothing was happening. I pressed harder and heard the engine, then noticed that the explosion had kicked the car out of gear, into neutral. And I had to scoop the glass out of the gear box and put it back into drive, and start driving normally. Then I went for the radio, asking the second car if they’re still alive. I think the whole thing was less than ten seconds, but it could also have been five minutes, I have no idea. Time in that moment did not make sense.

So I asked the others [in the second car], are you still alive? They actually thought we were dead, because they’d just seen the car disappearing, smoke and fire, and then coming out, getting slower and slower on the other side. And they couldn't look in the windows, like they were passing by too fast. Then the radio keyed up again, and they were like, ‘No, no, we’re all good. And I was like, OK, keep driving, keep driving, keep driving.’

We came towards the blockpost. They saw that something had blown up, and they saw two cars that were obviously damaged, coming out of that, and we're just honking our way through there. That was probably the fastest passing a blockpost ever.

They [the blockpost guards] jumped out of the way, and the cars made space. We came flying in, took a left turn, there's a gas station there, so we're like, ‘OK, stop at the gas station.’ Just for a look, because what you hear over the radio and what you see yourself is two different things.

So we got out of the car. The cars looked horrible, both of them. Shrapnel had hit the hood of our car, like smashed right through, and gone through the back out the light. So one metre further back, and we wouldn't be talking, because that was an actual piece of shrapnel from whatever blew up. I saw the other two, Anna [a German volunteer] and Daniel, and they looked okay, they were moving, there were no parts missing, no massive bleeding.

There were a bunch of Ukrainians at that gas station. They were all looking at me and telling me something, and I was like, ‘No, it's all good, it's all good.’ One was waving at me, and I was like, ‘What the fuck do you want?’ and it turned out he had my licence plate. So driving into the gas station, I’d lost the rear licence plate. The other one had been blown up earlier, but that fell off there.

I threw [the licence plate] in the car, and then okay, let's go to the hospital, which is about another three minutes away. So we're taking the lead again, and Vlada was trying to see, because the windshield was completely destroyed, both my mirrors were gone, and my window wouldn’t move, so I couldn't stick my head out. I was basically guessing where to go, and we were just honking the entire time to get people out of the way, which worked surprisingly well.

We kind of stopped on the intersection, because we noticed we missed the turn to the hospital, reversed back – reversing without mirrors is not fun, I would not recommend – and then drove to the hospital. I think at that point I actually know exactly what happened, because I was back on camera again.

Yeah, the whole thing from the explosion to the hospital was like, maybe like six minutes or something, because we know we were driving, we had photos and videos from driving out of Selydove, on the highway towards Novohrodivka, that was at X hour, and like fifteen minutes later, there's the first pictures of the destroyed cars, which [Anna and Daniel] took, because they were not majorly injured.

At the hospital they had to rip open the doors of the duster, because they were both jammed, to get the evacuees out. The cat was completely unharmed because Vlada had had both her arms around her – what’s why her arms were OK, because they were lower than the glass flying around. The cat was all right. There was another shock moment when we ripped open the door and the evacuee dude came out. He had shrapnel in his right arm and he was pressing his arm to his stomach and when he came out I just saw a large amount of blood on his shirt. I was like, ‘OK, come with me.’ [i.e. Lars thought the man had a serious abdominal injury; but it was just his arm.]

The evacuees got checked out first, and they took a bit of time to stitch that arm up, but that was that. We had two destroyed cars that couldn’t drive back home.

Probably the worst part was that I had been on the phone while driving, so I had my phone right here [in the breast pocket of his plate carrier], where I probably had a lot of shrapnel. I’d been on the phone with Lea [Lars’ partner and co-founder of UAU], about something we’d organised for the next day. I’d said I was already in the safe zone, or what was considered so at the time, and she just hears a boom and silence, and then all the rest. I have no idea when I put the phone back into my plate carrier, but it didn’t hang up. At the gas station or going to the hospital I realised I was still on a call. Lea was silent, just listening to everything that was happening, and she could obviously hear two voices, so there were two people still alive.

She was at an event with about 600 people who were hearing it live because she was on speaker. She basically tossed someone a key and was already in the car by the time I got back to the phone. I was like, ‘Hospital, Pokrovsk! We’re on the way, everyone’s alive.’ That was probably the worst part of it. I wouldn’t want to be the one on the phone a hundred kilometres away.

No fun. But yeah, everyone’s good, no major damage except for the cars.

Audio of the above interview:

What precautions have you taken since then?

There are so many things we’re preparing for, so many precautions – SOPs [Safe Operation Plans], plans, equipment and gear – but that particular time, there was literally nothing we could have changed. Or, the other way around, we could have done everything differently, like driving at 120kph instead of a hundred, so we’d have been way past when the thing blew up. Or ten minutes later it would have been different, like every single thing, which would probably have kept us from being there.

In terms of direct effect, we’re all upgrading our body armour, which is expensive, and looks ridiculous, because it looks like you’re really in a tank, but the more Kevlar you have around you, the better. This thing [in my neck] wasn’t shrapnel, it was just a piece of glass, and everything in the way would have slowed it down enough not to damage anything. But it’s not just the direct shrapnel from whatever weapon has been used, but also what you have around you, and what’s sitting in the cars. Usually on a mission we have the windows all the way down so we can hear better, and there will be less glass flying around, but on that particular one, we were about five minutes from the shelter [where the evacuees were headed]. We’d have got the people out of the car, and everything would have been good.

So I'm getting extra neck protection, yeah, and we're also working towards up-armouring the cars, or getting armoured cars, which is ridiculously expensive. The other thing is obviously drone jammers, because the day before we got hit, we got chased by two FPVs out of Novohrodivka. So, we had a very exciting weekend.

Do you often get chased by drones?

We try to avoid areas where there's heavy use of FPVs. The problem is, when the war started, they were used in and around the trenches, but then they slowly expanded the range, to two kilometers, then fifteen, and now there are isolated cases of FPVs up to thirty kilometres behind the lines. It hasn’t been confirmed yet, but supposedly there were FPV drones flying in Slovyansk, which is quite far away from the front, so it it’s technically possible [for the Russians] to use them quite far within our territory. So jammers are a must by now, and general situational awareness. Everyone else in the car looking into the sky all the times because the driver can’t.

We’ve seen a lot of drones, especially during evacuations, but it’s mostly reconnaissance drones, like the classic Mavic just flying around looking for people. Before the rise of FPV drones that was OK. In a village about five kilometres from the enemy line we had a drone directly above us, which could have been a friendly one, but about five or ten minutes later, artillery started hitting that spot. So we started to move a lot faster with distributions, four or five of them, and the drone kept following us, and artillery had exploded behind us, so we were like, ‘All right, fuck this shit, we’re getting out of here.’

How much did the drone jammers cost?

The set we now have, which covers most frequencies but sadly not all, was just under 400,000 hryvnia, about 8,200 euros. So it’s very expensive. You can buy a car for that, a good car in good condition!

After the attack, would you consider quitting?

No, that thought actually did not cross my mind. We definitely take more precautions and we’re more careful, and we slowed down in that region, because first getting chased by FPVs, then getting blown up is probably not a coincidence. We did one more evac in Selydove, then stayed away from the entire area for at least a week. Also, we were short on cars!

Donations can go through one of UAU’s partners in Germany, Lift Ukraine. Or to Lars’ fundraiser.

Next: an interview with Vlada, UAU’s Ukrainian translator.

I am shivering. I know how it happens that one goes through some hard experiences with a cool head and common sense, not panicking, but a moment comes afterward when the full impact of the event knocks on the door and demands reckoning. I am really glad that, as it seems, Ceiling Cat was watching over the cat and the humans who were bringing him/her to safety...

Article reminds me of the drone strike we had here in the U.S. last Tuesday night. Sorry, could not resist the comparison. It is sobering reading how close Lar's ticket got punched. For sure Russia is guilty of terrorism which is in line with their Stalinist history.