Of course, the answer varies by location. A village near the Hungarian border is safer than a trench on the frontline. What’s harder to grasp is ‘how dangerous’ places in between are, and what that might even mean, for ordinary people who just want to go about their daily lives and raise families without getting murdered.

Disclaimer: I can only speak from my limited personal experience as a foreign visitor. Every Ukrainian will have their own story.

Cities

Unless there is the element of surprise, as with the initial attack on 24 February 2022, it takes an army a long time to grind its way towards a city. Consequently, unless and until you are occupied - which is a whole different, horrific matter - the danger is not from ground attack but from the skies, the ‘air raid’, though actually that term doesn’t fit Ukraine the way it fitted, for example, the Blitz in London, where German planes flew overhead releasing bombs that relied on simple gravity. That happened to cities like Mariupol and Kharkiv in the early days of the war, but thankfully the attackers no longer dare to do that as their planes would be shot down.

Most cities have to worry about two main kinds of attack:

Drones: usually Shaheds or ‘mopeds’ (so called because of the sound they make) are slow-moving but difficult to shoot down because they are small. These generally crash into buildings and cause relatively small explosions.

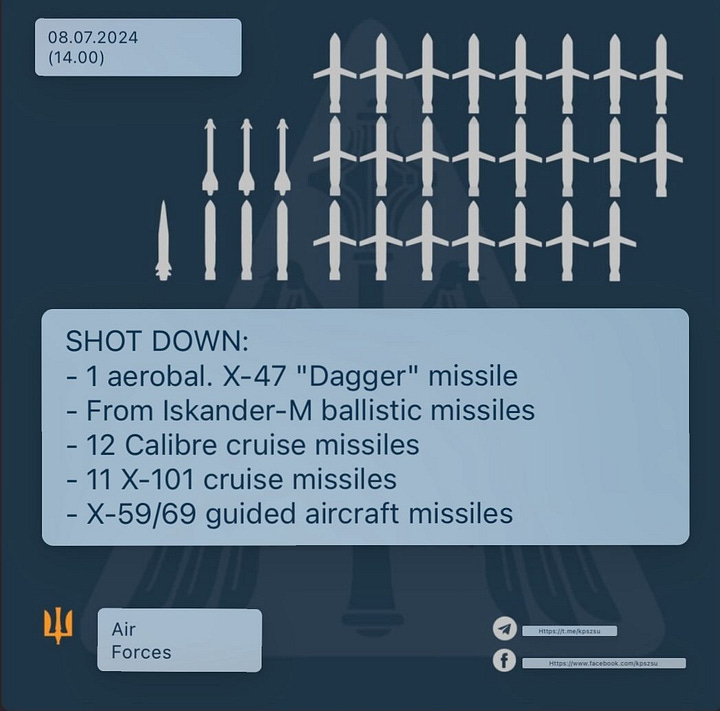

Missiles is a big category, ranging from older cruise missiles to modern ‘hypersonic’ projectiles. The latter are favoured by the Russians for taking out particularly threatening military targets, such as Okhmatdyt Children’s Hospital in Kyiv. They are not impossible to shoot down, but it’s hard, and Russia will often send swarms of drones or more conventional missiles in an attempt to exhaust or confuse air defence beforehand.

So if you’re in a city just trying to travel to work or get a night’s sleep, what do you do? Some observations from the places I’ve visited.

Lviv – the west

I’ve heard people joke that in Lviv if the siren sounds you have time to finish your dinner before strolling down to the shelter. This is unfortunately not quite true, as the fastest type of Russian missile, the Kinzhal (‘Dagger’) can travel at 12,350 km/h; but actually not all air alerts mean ‘something is about to hit you’. The alert is also sounded if Russian warplanes take off and start manoeuvring in a way that suggests they are going to fire at Ukraine. So in practice Lvivians usually get enough notice to pack up and go somewhere rather than just having to sit or run, particularly as most missiles are in fact slower. At time of writing, Lviv has had a mere 600 air alerts since 24 February 2022, compared to Kharkiv’s 4,511.

Lviv is big, and relatively rarely do missiles/drones actually a) target it or b) make it that far. So do you head for bed after dinner – as most missile attacks occur in the small hours – or for the shelter in case it’s a bad night? On the one hand, it’s a relatively controlled, plannable, decision. On the other, it’s a drawn-out, dragging stress.

Kyiv – the centre

The capital is obviously a focus for Russian attacks. For example, no less than eighty-nine drones were launched at Kyiv on the night of 30 July 2024.

And all were shot down, remarkably, though that isn’t always the case, and even when it is, debris can be lethal. Kyiv has the country’s best defences, though it’s also subjected to some of the largest and most sophisticated attacks, such as the Okhmatdyt atrocity.

What this means on a daily basis in 2024 is that while some nights the sky is lit up and there are bangs as air defence fires at drones, there are seldom large explosions. As well as reporting when planes take off hours before launching missiles, once they are launched Ukrainian air defence is capable of identifying what kind they are, plus there is a plethora of Telegram groups supplying information about what is going where; everything from official Air Force updates to people reporting what they just saw fly over their house. So again you have some awareness of what’s coming - if you put the time and mental/emotional energy into investigating.

People have different thresholds for what they consider a bad enough threat to react to at all, or in what way to react. If you live near a Metro station you might decide to head down there if there is a report of bombers taking off and moving towards positions where they are likely to aim at Kyiv. If you’re Galochka (who I generally stay with in Kyiv), you might roust the foreigner out of bed in the small hours if it’s been quiet for a couple of weeks but suddenly missiles are expected; because this might mean the enemy has been saving up expensive missiles for a murder bonanza. You then pile up cushions and sit in the corridor scrolling Telegram, watching reports of the wretched things lurching around Ukrainian airspace in a preprogrammed attempt to create doubt about where they are going before – probably – getting shot down. And at some point you just have to go back to bed. ‘Let them kill us, then! I’ve had enough,’ to quote Galochka at five o’clock one morning in autumn 2023.

This sounds almost mundane; almost flippant. Which is deliberate: it’s a survival mindset. You cannot exist in a constant state of terror/alert. Galochka survived the siege of Mariupol; she’s not going to crack now, Russians.

Yet for, say, one in 10,000 people lack of caution - or the need to do a job that cannot be done from a metro station - does lead to death, because even if a drone is shot down there is debris, and Russia uses its most sophisticated weaponry to attack civilian infrastructure like power stations and hospitals.

Zaporizhzhia – the (south-)east

Zaporizhzhia city is about 30km from a part of the front line that has been stable since the early days of the full-scale invasion. In my experience there are a couple of strikes a week on the city, which is quite sprawling and, being a Soviet industrial town, lacks a historical centre on which Russia can focus attacks aimed at destroying Ukrainian culture. However, the sirens go off frequently because of fighting not far to the south, and drones/missiles flying over the region to cities further inside Ukraine. According to the Alerts in UA site - an excellent real-time resource if you’re outside the country, and an historical resource everywhere - Zaporizhzhia had 189 alerts in July 2024.

Air force monitoring is sophisticated enough to indicate in various ways whether the city itself is under threat, and how direct/swift/serious the threat is, but who’s going to grab their phone six times a day, including at three in the morning, and consult a combination of sites and groups to determine what is most likely to be going on? I guess someone probably does that, but I doubt many do. Because attacks are more likely from around 11pm into the small hours, you might check more closely at that time. My friends who live near the hydroelectric dam (a favourite Russian target) don’t have an internal corridor and do happen to have an official shelter in the cellar at the bottom of their pid’yizd (apartment block staircase), so they go down there some nights – and sure enough a missile struck just a few blocks away from them, though their building wasn’t damaged. When staying with other friends in their ground floor apartment, I take my cue from them, and the agreed rule is that if a strike is close enough to cause vibrations that set off car alarms, you go and sit in the corridor (and probably glue yourself to Telegram there).

Which is certainly not to say missiles and drones never do hit Zaporizhzhia city in the daytime. This happens often enough for it not to be a sensation, but nor is it background noise like in Kharkiv. Which, like a lot of situations in wartime Ukraine, results in a kind of black comedy. For example, one morning in the flat…

THUD

Silence.

Slowly people come out of their rooms into the flat corridor.

‘Did you hear that?’

‘Yes.’

‘An explosion.’

‘Where was it?’

‘I reckon about [location].’

‘Could be.’

‘I’ll look it up online.’

‘Yes.’

Pause.

Everyone goes back to their rooms.

That exchange is slightly edited down, but not very much.

Because what else is there to say? ‘Oh dear, some of our neighbours have just been murdered by the genocidal horde that has laid waste to swathes of the country to the south and east of us. I hope the emergency services help the survivors, and there isn’t a double tap that kills them too.’ But that’s the thought that hits everyone the moment the missile strikes. No need to rub salt in the wound by saying it aloud.

Zaporizhzhia does have shelters, but apart from the obvious one in my friends’ pid’yizd I’ve never registered where one is, as opposed to almost certainly strolling mindlessly past dozens of signs.

Below is a typical lockscreen for someone in Ukraine. The background image is your loved one (in my case, my husband), and then the endless alerts. The advice to charge your gadgets is in case the electricity grid is damaged.

The difference between my lockscreen and that of a fortysomething Ukrainian woman is that my husband is safe a thousand miles away, while her partner may well be at the front. Or dead.

Kramatorsk - the east

I only spent one day in Kramatorsk, which is in free Donetsk and gets bombarded in a similar way to Kharkiv, but I saw these shelters on the street. If I were in Kramatorsk and heard an explosion nearby I probably would scoot into one.

Kharkiv: the (north-)east

Kharkiv has been constantly and relentlessly battered. For six months at the start of the war it was within range of Russian artillery (about fifteen miles), which is the most destructive kind of bombardment, because it’s cheap and therefore simply keeps coming. If the Russians had got within artillery range in the renewed assault in May 2024, I would have left the city; this is considered by a lot of civilian foreign volunteers to be the tipping point.

That did not happen, but nevertheless there’s a new menace in Kharkiv, and other cities near the front line such as Kramatorsk: guided (glide) bombs, which are old Soviet bombs with fold-out wings and satellite navigation added. To quote the BBC explainer, these are for ‘devastating cities on the cheap’. Their range is limited to 40 miles, so many cities are out of their range, but Kharkiv is not. The largest glide bombs are capable of destroying a seven-storey building.

In July 2024, Kharkiv experienced a mere 85 air alerts, as opposed to Zaporizhzhia’s 189. Unfortunately, that’s because in Kharkiv, they last longer. I think the record-holder is 50 hours. Those 85 alerts lasted a total of 26 days, 13 hours – in one 31-day month. Zaporizhzhia racked up a mere 7 days and 7 hours.

So what do you do when the siren starts blaring in Kharkiv? Well, you often have to listen for the first rise and dip to work out whether it’s the start of an alert or the all-clear, because you can’t bloody remember. Then there might be an explosion during the sirens, or there might have been one just before, or there might be one just after, or all three. Or there might be no sirens because of electricity blackouts, a problem all over Ukraine as Russia bombards the energy grid. In Kharkiv it sometimes feels like the main function of the system is to show up who only just arrived in town - at which point the ‘extreme alert’ automatically installs itself on your phone - when their bag starts wailing in the supermarket.

I was in a tram one morning when there was a typical thud in the middle distance. One person exclaimed ‘whoa!’ and everyone else was silent. For three seconds. Then everyone started shifting and chatting as they had before, all at the same time. The three seconds’ silence was not shock or panic, it was the amount of time you need to first brace for a blast wave and then establish it’s not coming. Then you go back to normal.

Odsesa - the south

I haven’t travelled much in the south of the country, some of which is also badly affected. But the city of Odesa is covered, along with Kramatorsk and Kharkiv, in a longer article about people’s attitudes by a Ukrainian journalist, geared at explaining the situation to outsiders: Why Some Ukrainians Choose to Ignore Air Raid Sirens.

What all this shows is that the classic ‘air raid’ situation of people running for a designated underground building with a big sign on it the moment the sirens start blaring is mostly redundant. Yet if you’re abroad, trying to determine how much danger your relatives or friends are in, it can be hard to understand how things actually work in a given area.

Also, it can be painful to realise, but sometimes Ukrainians will not even want foreign friends’ concern every time a missile happens to strike their city, because it’s one more thing for them to handle. Five messages about your feared death to reply to at the same time as trying to get a cold breakfast for the kids and then labour down nine flights of stairs because the electricity’s off again. Others, of course, treasure every manifestation of friends’ concern and support. Everyone’s different.

The sophistication of warning techniques, the advance notice, the ability to differentiate between different kinds of threat – in most ways this is an improvement on the ‘Everyone to the shelters!’ panic-and-run situation. In others, well, it’s simply exhausting. It’s the nature of modern warfare that the entire country is potentially under threat all the time. For two and a half years. It’s not surprising some people just don’t react at all any more.

The most gripping and moving accounts of war are often about the mundane activities of citizens and, in this case, visitors. Thank you for revealing this, Anna.

***sigh***

and also ***damn***